This online and downloadable resource was developed as part of the ongoing work of the Alliance to Advance Comprehensive Integrative Pain Management. This was a collaborative effort among the Spiritual Care subgroup members that initially met in 2018-19 after the second Pain Policy Congress. These members came back together recently to update and complete this piece so that it can be shared more widely.

Authors: Christina Puchalski, MD, Bonnie Sakallaris, PhD, RN, Matthew J.Taylor, PT, PhD, C-IAYT, Juliana Lesher, M.Div., Ph.D., BCC, Mindy Wallace, DNP, MSN, CRNA, DAIPM, Amy Goldstein, MSW, Col. Kevin Galloway, BSN, MHA (RET)

All patients in an integrative pain practice should have their spiritual care needs assessed and receive spiritual care as needed and desired. Evidence in multiple studies demonstrate that patients want this care and that addressing spiritual needs improves physical, functional, and emotional outcomes.1-5 Many national and international guidelines have been developed for addressing spiritual care as part of whole person care. 6-12 The clinical models described in these guidelines are based on addressing spirituality as part of wellness but also identify spiritual distress as part of symptom management.12 In these guidelines spirituality is defined broadly as a “dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.”6 Religion is one type of expression of spirituality and it relates to the participation in beliefs and practices of a community of faith, and usually focused on a relationship with God or a higher power. 13 Spirituality has been demonstrated to impact health outcomes including pain, pain interference, pain catastrophizing, quality of life, and has been associated with decreased mortality and morbidity.14-16 Studies also demonstrate association of spiritual distress with worse quality of life, physical pain, depression and anxiety.

All patients in an integrative pain practice should have their spiritual care needs assessed and receive spiritual care as needed and desired. Evidence in multiple studies demonstrate that patients want this care and that addressing spiritual needs improves physical, functional, and emotional outcomes.1-5 Many national and international guidelines have been developed for addressing spiritual care as part of whole person care. 6-12 The clinical models described in these guidelines are based on addressing spirituality as part of wellness but also identify spiritual distress as part of symptom management.12 In these guidelines spirituality is defined broadly as a “dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices.”6 Religion is one type of expression of spirituality and it relates to the participation in beliefs and practices of a community of faith, and usually focused on a relationship with God or a higher power. 13 Spirituality has been demonstrated to impact health outcomes including pain, pain interference, pain catastrophizing, quality of life, and has been associated with decreased mortality and morbidity.14-16 Studies also demonstrate association of spiritual distress with worse quality of life, physical pain, depression and anxiety.

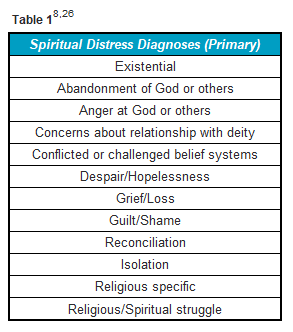

The experience of pain involves multiple signals influenced by the biochemical pain pathways, cognition, emotions, environments, and behaviors. Each of these pathways can reduce or increase the experience of pain.15 The experience of chronic pain is multi-dimensional, including physiological and existential suffering, such as questioning why I have to go through this painful existence.17 It is not surprising then that studies have shown that prayer was either the primary or second most frequently used coping mechanism to deal with pain.15 The need for intervention in the spiritual or existential dimension of pain appears to be common across nationality, belief systems, and cultures.17-22 There is significant evidence documenting spiritual pain and its relationship to other forms of pain as well as the influence of spiritual distress and spiritual coping on the pain experience.23-25 Spiritual pain can be defined as pain deep in the soul. It is one dimension of what is now understood as the multi-dimensionality of pain. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP) have developed spiritual distress diagnosis (Table 1).8,26

The experience of pain involves multiple signals influenced by the biochemical pain pathways, cognition, emotions, environments, and behaviors. Each of these pathways can reduce or increase the experience of pain.15 The experience of chronic pain is multi-dimensional, including physiological and existential suffering, such as questioning why I have to go through this painful existence.17 It is not surprising then that studies have shown that prayer was either the primary or second most frequently used coping mechanism to deal with pain.15 The need for intervention in the spiritual or existential dimension of pain appears to be common across nationality, belief systems, and cultures.17-22 There is significant evidence documenting spiritual pain and its relationship to other forms of pain as well as the influence of spiritual distress and spiritual coping on the pain experience.23-25 Spiritual pain can be defined as pain deep in the soul. It is one dimension of what is now understood as the multi-dimensionality of pain. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP) have developed spiritual distress diagnosis (Table 1).8,26

Recommendations are for attending to all dimensions of patient’s distress and wellness including spiritual distress and wellness.2,27 Therefore comprehensive care requires the evaluation, assessment, and inclusion of spiritual care in the plan of care. The consensus-based guidelines have agreed that all healthcare practitioners should be involved in spiritual care.28,29

The practice of spiritual care is based on a generalist-specialist model of care called the Interprofessional Spiritual Care Model.30 ‘Spiritual care involves the assessment and treatment of spiritual distress, support for spiritual resources of strength and in-depth spiritual counselling when appropriate’.31 Clinicians address spiritual concerns, do spiritual screening or histories to assess for spiritual distress and work with spiritual care specialists such as chaplains, pastoral counselors, or spiritual directors in treating and attending to spiritual distress. Health care chaplains have the skill and expertise to assess and address the spiritual and existential issues frequently faced by pediatric and adult patients with acute or chronic pain or receiving palliative care. Chaplains play a strong role as professional members of the health care team. Spiritual care is best provided in an interdisciplinary, team-based care environment with strong ties to the communities they serve.29,32 In the community setting the spiritual care expert may be clergy, pastoral counselors or spiritual directors.

Spiritual care builds on the relationship between clinician and patient and is facilitated by the practice of compassionate presence.29 Spiritual care or “treatment” is individual, dependent on the patient’s beliefs, culture, and values.29 Spiritual care may include such practices as reflective listening, guiding first person ethical inquiry, and being present to patients. Treatment options might include referral to spiritual care professionals, art therapists, meaning-oriented therapy, meditation. If the patient identifies specific spiritual or religious practices that are important to them, then encouraging those practices might be appropriate, such as reconnecting with nature, prayer, meditation, community support, rituals. Part of positive coping strategies might include spiritual coping strategies such as meditation or re-establishing priorities.15,28,29,33

The outcomes of spiritual care are the individual’s ability to understand their suffering at a deeper level, while making some sense of the pain experience, and to give the experience a meaningful place within the overall context, direction, or purpose of their life. Accompanying a patient in the midst of their suffering may help that patient cope better with their overall condition. Eric Cassell has noted “Transcendence is probably the most powerful way in which one is restored to wholeness after an injury to personhood. When experienced, transcendence locates the person in a far larger landscape.”34

Offering spiritual care supports outcomes that can include peacefulness, a sense of coherence, and less depression and anxiety, as well as improved pain management. The acknowledgment and inclusion of spiritual care in the CIPM definition represents a significant milestone in understanding the complexity of pain care while also satisfying the preferences of those living with pain.

References:

- Exline JJ, Krause SJ, Broer KA. Spiritual Struggle Among Patients Seeking Treatment for Chronic Headaches: Anger and Protest Behaviors Toward God. Journal Of Religion And Health. 2016;55(5):1729-1747.

- Nsamenang SA, Hirsch JK, Topciu R, Goodman AD, Duberstein PR. The interrelations between spiritual well-being, pain interference and depressive symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal Of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;39(2):355-363.

- Garschagen A, Steegers MAH, van Bergen AHMM, et al. Is There a Need for Including Spiritual Care in Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation of Chronic Pain Patients? Investigating an Innovative Strategy. Pain Practice: The Official Journal Of World Institute Of Pain. 2015;15(7):671-687.

- Baetz M, Bowen R. Chronic pain and fatigue: Associations with religion and spirituality. Pain Research & Management. 2008;13(5):383-388.

- Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient education and counseling. 2015;98(11):1320-1328.

- Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, Reller N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(6):642-656.

- World Health Organization: Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. Paper presented at: WHO Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly 2014.

- Domain 5: Spiritual, Religious, and Existential Aspects of Care. In: National Concensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th Edition. Vol 2020.

- Meaningful Ageing Australia. National Guidelines for Spiritual Care in Aged Care. Parkville: Ageing Australia;2016.

- Selman LE, Harding-Swale R, Agupio G, et al. Spiritual care recommendations for people receiving palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa: With special reference to South Africa and Uganda. London: Cicely Saunders International;2010.

- NHS Chaplaincy Guidelines 2015: Promoting Excellence in Pastoral, Spiritual & Religious Care. 2015.

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885-904.

- Appleby A, Wilson P, Swinton J. Spiritual Care in General Practice: Rushing in or Fearing to Tread? An Integrative Review of Qualitative Literature. Journal Of Religion And Health. 2018;57(3):1108-1124.

- McCabe R, Murray R, Austin P, Siddall P. Spiritual and existential factors predict pain relief in a pain management program with a meaning-based component. Journal of Pain Management. 2018;11(2):163-170.

- Wachholtz AB, Pearce MJ. Does spirituality as a coping mechanism help or hinder coping with chronic pain? Current Pain And Headache Reports. 2009;13(2):127-132.

- Siddall PJ, Lovell M, MacLeod R. Spirituality: What is Its Role in Pain Medicine? Pain Medicine. 2015;16(1):51-60.

- Shukla S. Spirituality in Ayurveda. Spirituality in Clinical Practice. 2020;7(2):103-113.

- Ferreira-Valente A, Damião C, Pais-Ribeiro J, Jensen MP. The Role of Spirituality in Pain, Function, and Coping in Individuals with Chronic Pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass). 2020;21(3):448-457.

- Andersen AH, Assing Hvidt E, Hvidt NC, Roessler KK. Doctor–patient communication about existential, spiritual and religious needs in chronic pain: A systematic review. Archiv für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion. 2019;41(3):277-299.

- Vasigh A, Tarjoman A, Borji M. Relationship between spiritual health and pain self-efficacy in patients with chronic pain: A cross-sectional study in west of Iran. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020;59(2):1115-1125.

- Bullington J, Nordemar R, Nordemar K, Sjöström-Flanagan C. Meaning out of chaos: a way to understand chronic pain. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences. 2003;17(4):325-331.

- Zander V, Eriksson H, Christensson K, Müllersdorf M. Rehabilitation of women from the Middle East living with chronic pain–perceptions from health care professionals. Health care for women international. 2015;36(11):1194-1207.

- Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Hui D, De la Cruz MG, Thorney S, Bruera E. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. The American Journal Of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2013;30(5):455-461.

- O’Neill MT, Mako C. Addressing spiritual pain. Health Progress (Saint Louis, Mo). 2011;92(1):42-45.

- Park CL. Religiousness/spirituality and health: a meaning systems perspective. Journal Of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30(4):319-328.

- NCCN Guidelines for Patients: Distress®. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/distress-patient.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- Harris JI, Usset T, Krause L, et al. Spiritual/religious distress is associated with pain catastrophizing and interference in veterans with chronic pain. Pain Medicine. 2018;19(4):757-763.

- Kruizinga R, Scherer-Rath M, Schilderman HJBAM, Puchalski CM, van Laarhoven HHWM. Toward a Fully Fledged Integration of Spiritual Care and Medical Care. Journal Of Pain And Symptom Management. 2018;55(3):1035-1040.

- Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, Reller N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. Journal Of Palliative Medicine. 2014;17(6):642-656.

- Puchalski C, Jafari N, Buller H, Haythorn T, Jacobs C, Ferrell B. Interprofessional Spiritual Care Education Curriculum: A Milestone Toward the Provision of Spiritual Care. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(6):777-784.

- Puchalski CM, Sbrana A, Ferrell B, et al. Interprofessional spiritual care in oncology: a literature review. ESMO Open. 2019;4(1):e000465-e000465.

- Handzo G, Koenig HG. Spiritual care: whose job is it anyway? Southern Medical Journal. 2004;97(12):1242-1244.

- Balboni M, Puchalski C, Peteet J. The Relationship between Medicine, Spirituality and Religion: Three Models for Integration. Journal of Religion & Health. 2014;53(5):1586-1598.

- Cassell EJ. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. Loss, Grief & Care. 1998;8(1-2):129-142.

Related Article:

The Connector – Spotlight: CMS Approves New HCPCS Codes for Spiritual Care

Related Article:

15th Annual GWish Art of Presence Healthcare Renewal Retreat [Virtual]

Trackbacks/Pingbacks